“We need to educate the people about their rights and how to fight for them.”

~ Bruce Eriksen (1)

* * *

The history of

the Downtown Eastside

is a history

of the struggle

for human rights.

First Nations people

have fought for a just

land claims settlement

for over one hundred years,

and we take inspiration

from their example,

especially in these dark days

when we feel

we are losing control

of our lives

to global economic wars,

or mega-projects

that overwhelm our neighbourhoods.

In the Downtown Eastside

working men and women

fought for the eight hour day

and the right

to form trade unions.

The Vancouver and District Labour Council,

one of the oldest Labour Councils in Canada,

started in 1889.

In 1903, Frank Rogers

was picketing for

the striking United Brotherhood

of Railway Engineers

when he was shot and killed

by a C. P. R. hired guard

at the food of Gore Avenue.

In 1918, Canada’s

first General Strike

took place in Vancouver

to protest the murder

of Ginger Goodwin,

a labour organizer

from Cumberland, B. C.

In 1919, there was

another General Strike

in sympathy with

the Winnipeg General Strike

during the Great Depression

of the 1930s.

Unemployed men

in the Downtown Eastside

fought for the right

to food, shelter,

work and wages.

In April, 1935,

Mayor McGeer read the Riot Act

at Vicotry Square

to two thousand

unemployed men.

Willis Shaparla was there,

and he commented,

“When hungry Canadians

were asking for food,

McGeer read us the Riot Act.”

Soon after the occupation

of the Carnegie Museum

by three hundred unemployed workers

in May, 1935,

the men of the

Relief Camp Workers’ Union

began the On-To-Ottawa Trek.

Then in June of that year

one thousand longshoremen

were attacked by police

near Ballantyne Pier

as a result

of a lockout and strike.

Longshoremen had been fighting

for their own union

since the 1800s,

and by 1944 they had a strong union

that protected their rights.

On May 20, 1938,

unemployed men looking for relief

occupied the Vancouver Art Gallery,

the Georgia Hotel

and the Post Office

at Granville and Hastings.

Gradually, the occupation

shifted to the Post Office

which the police attacked

on June 19th.

Over one hundred men were hurt

in the ensuing struggle.

That night ten thousand people attended a rally

at the Powell Street Grounds,

now called Oppenheimer Park,

in support of

the homeless, hungry men.

In September, 1939,

the Government of Canada

would ask these unemployed men

to fight for their country.

They did fight,

and many of them

had the dream

of a better Canada

after the war was over.

In 1995, federal public servants

occupied the old Post Office,

now the Sinclar Centre,

to protest a federal budget

that planned to throw

fifty thousand of these workers

into the anguish of unemployment.

Chinatown and Japantown,

called Powell Street by citizens

of Japanese background,

were also part of

the Downtown Eastside.

At first people lived

in these communities

because they weren’t allowed

to live anywhere else,

but as the years went by,

Chinatown and Japantown

became centers of resistance

against injustice,

and they shaped their history

with courage and endurance.

From 1881 to 1885

Chinese labourers helped build

the Pacific Section

of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

At least six hundred

Chinese workers died

building that track.

In 1887, three hundred white men

beat up a camp

of sleeping Chinese workers

at Coal Harbour.

In 1907, another race riot

Broke out, and a violent mob

Rampaged through Chinatown

and Japantown.

During the Great Depression

one hundred and seventy-five

Chinese people

died of starvation in Chinatown. (2)

After the attack

on Pearl Harbour

on December 7, 1941,

the federal government

uprooted the entire population

of Canadian citizens

of Japanese origin,

and moved innocent people

to internment camps

with no regard

for human rights

or family ties.

True, the war was

going badly in 1941.

Before the end of the year

nearly two thousand Canadians

were killed or captured

when Japanese troops

entered Hong Kong.

Panic, and fear of

a race riot,

may explain the action

of the Canadain government,

but they do not excuse it.

Not one Canadian

of Japanese origin

was found guilty

of any offence

against the security of Canada

throughout the war.

After a long fight

for human rights,

Japanese Canadians won redress,

and on September 22, 1988,

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney

formally apologized

on behalf of

the Government of Canada

for wrongfully interning

and seizing the property of

Canadians of Japanese background.

Although Japantown never regained

Its prewar size,

the Powell Street Festival

has become an annual celebration

of the Japanese Canadian community,

and Chinatown has become

a busy social, commercial

and tourist centre

with a highly respected

international reputation.

In 1968 the Strathcona

Property Owners and Tenants

Association (SPOTA),

was formed to stop

the disastrous urban

renewal plans of city Council.

SPOTA stopped the bulldozers

and saved Strathcona.

Bessis Lee of SPOTA remarked,

“We have to remind the city

that when they decide

to change things in a community,

they must always consider

the total planning

of that community,

and the concerns of the people

who live in it.” (3)

The Downtown Eastside

Residents’ Association (DERA)

would agree with that statement.

Since the early 1970s

DERA has fought

to establish the right

of the community

to change its image

from skid road

to the Downtown Eastside

and to win

much needed services

for the members of

Vancouver’s oldest neighbourhood.

“The people who live here,

they call it the Downtown Eastside,”

Bruce Eriksen said,

and in 1983

Mayor Harcourt of Vancouver

presented a civic award to DERA

which declared that

this citizens organization

had helped to change

the perception of

part of Vancouver,

formerly known as skid road,

to the Downtown Eastside.

In the 1980s, DERA,

with Jim Green as organizer,

addressed the right to housing

in the Downtown Eastside

by building low income housing.

The DERA Housing Co-op

was completed in 1985,

and the Four Sisters Co-op

was finished in 1987.

In the 1970s, citizens

of the Downtown Eastside

fought for seven years

to win the Carnegie Community Centre

for the neighbourhood.

Later, they won Crab Park,

and in 1985, they started

the Strathcona Community Gardens

which empowered the community

through the creative act

of planting seeds.

Downtown Eastside poets,

such as Tora and Bud Osborn,

and the Carnegie Newsletter,

edited by Paul Taylor,

gave a powerful voice

to the community,

as did the books of Sheila Baxter.

This writing showed

that human beings

could forcefully reject

the negative image

ascribed to them,

and replace it

with a community of caring

that speaks from the heart.

In 1995, the Downtown Eastside,

in co-operation with friends

all over Vancouver,

defeated a casino mega-project

that would have done great harm

to both the community

and the City of Vancouver,

and in recent years

the Vancouver Area Network

of Drug Users (VANDU),

the occupiers of Woodward’s

in the Woodsquat campaign,

homeless people in tent villages,

and Latinos in Action,

have fought courageously

for respect, dignity,

and the opportunity

to lead a meaningful life.

Remember also the glorious

Downtown Eastside Community Play

that was part of the celebrations

for the Carnegie Library’s 100th birthday

in the year 2003.

This play expressed the energy

and the caring

of our beloved community.

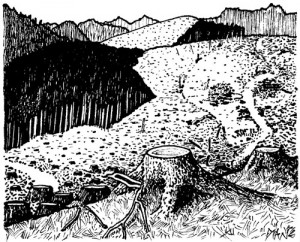

Now the Downtown Eastside

is under siege

from the gentrification

that has destroyed

many inner city neighbourhoods.

The fight for survival

is a desperate one, as developers,

in their haste for profit,

dehumanize the people who live here.

A discussion paper

prepared for the

Gastown Improvement Society in 1992,

referred to Downtown Eastside residents as

“those social service clients who frequent the area.” (4)

A Simon Fraser University instructor,

when talking of the human beings

who call the Downtown Eastside

their home, said,

“they get moved along’

they get kicked out.

Those poor buggers

are used to it.

They always get disenfranchised. (5)

When men of great power

deny the humanity of human beings

and the history of a community,

they tend to think

that they can destroy

both the people

and the place

without moral qualms.

The Downtown Eastside has

a long history, however,

and a rugged identity.

It is not expendable,

and it is not just skid road.

We are strong

when we stand in solidarity

with those who have fought

For human rights

for over one hundred years.

Memory is the mother of community.

~ Sandy Cameron

* * *

(1) Quoted in Hasson, Shlomo, and David Ley—Neighbourhood Organizations and the Welfare State, published by the University of Toronto Press, 1994, chapter 6, “The Downtown Eastside: ‘One Hundred Years of Struggle,’ page 178.

(2)Vancouver’s Chinatown—Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875-1980, by Kay J. Anderson, page 143.

(3)An interview with Bessie Lee in the book Opening Doors, Vancouvers’ East End, by Daphne Martlett.

(4)Carnegie Action Project Newsletter, September 15, 1996.

(5)”Gastown ideal for single women,” by Fiona Hughes, the Vancouver Courier, January 21, 1996.